Co-Existance

Life in some families is not shaped by a single diagnosis or one steady anchor. It’s shaped by difference itself, ordinary and constant, the condition of being together.

“Co-Existence”

It sounds like politics. Rivals who agree not to fight. States that share a border without sharing a future. But inside a family sharing multiple physical and neurodiverse challenges the word means something else. Diagnosis is not the exception.

It’s the air.

Children with different labels under one roof. Parents whose bodies carry their own. A house where silence is one person’s language, wheels are another’s freedom, and pain shadows a third. Outsiders look for the “normal” anchor, the one who steadies the rest. But what if there isn’t one?

What if stability comes not from sameness, but from multiple differences bound together?

Morning shows it most clearly. One already pacing, another heavy with fatigue that didn’t lift overnight, a third waiting for the world to soften enough to join in. Parents stand halfway between kettle and calendar, measuring spoons and minutes, deciding which thing will break if this small decision is wrong.

Socks become negotiation. Life becomes negotiation. The route to the door is never a straight line. It’s a path threaded through what each body can carry today.

Some people want a centre. They look for the one who is typical, who can translate, who will comply. They expect to find the gravity of normality holding everything in orbit. But families like mine don’t have a single pull.

We have many. There’s only spin, each of us with a different weight, sometimes colliding, sometimes circling apart but always returning to the same table.

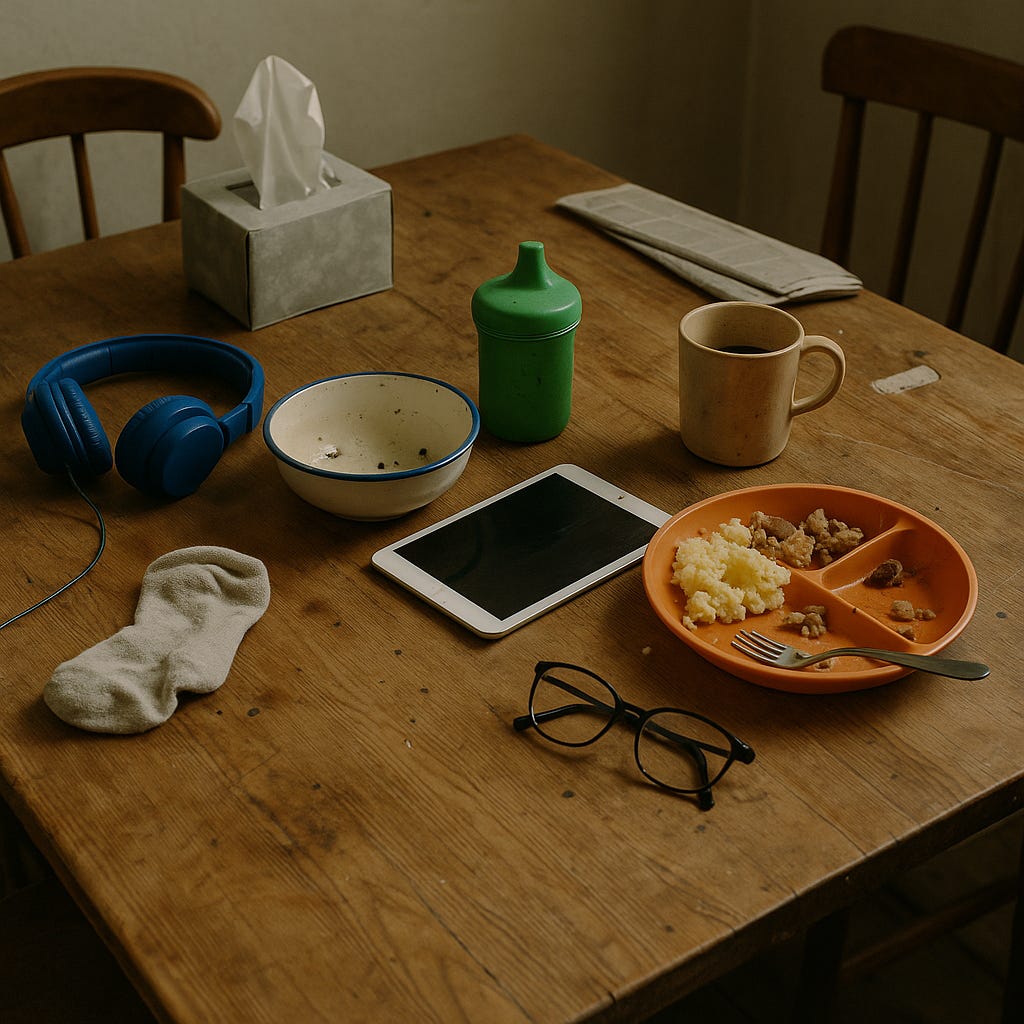

The table matters. It’s where the day is reassembled. Cut food smaller. Offer the cup with the right lid. Remove the tag that scratches. Slide the tablet closer because speech is not ready.

This isn’t drama. It’s the ordinary work of fitting life to bodies that don’t fit the default size. People say resilience like it’s a medal. It’s not. It’s a set of small decisions repeated until the pattern holds.

Disability doesn’t arrive as a guest. It doesn’t knock politely, take one seat, and leave the rest untouched. It runs in the wiring, in the blood, in the parent who carries pain quietly so the morning can continue, in the child who can’t yet say why the noise burns.

It doesn’t ask for space. It’s the space.

We’re told to aim for balance. Equal time for each child. Equal share of attention. Equal weight for the adults. Balance is the wrong metaphor. A scale suggests that if one side goes up, the other must go down.

Families like mine don’t hold a scale. We hold a chorus. Sometimes discord, sometimes harmony, never a single voice.

Listen closely and you can hear the rules the chorus keeps. There’s a hum that means safe and a silence that means trusted. There’s a footfall in the hallway that means pressure has risen and the need to reroute before something cracks.

We learn the timing of these cues the way other people learn timetables. Not because we chose to, but because the house demanded fluency.

The myth that harms us most is the myth of the anchor. The idea that there’s one steady person who stands on dry ground and holds everyone else in place. This myth turns parents and children into both symbols and tools simultaneously.

It can’t admit that the person who steadied yesterday may be the one in pieces today. It can’t see that endurance moves. In our house, roles circulate.

Protector, learner, translator, carried and carrier. Each one of us is all of these across a week.

To outsiders this looks like chaos. It’s not chaos. It’s circulation. It’s co-existence.

But circulation doesn’t mean it works every time. One child needs the house quiet to function. Another needs to hum, to move, to make noise in order to stay regulated. There is no volume setting that serves both.

Some days we solve it with headphones, separate rooms, timing the day so the overlap is brief. Other days we don’t. Someone’s need goes unmet, and they know it, and I know it, and the guilt of choosing sits in my chest like a stone.

This is not a design problem with a clever answer. It’s two bodies asking the same space for opposite things, and the space can’t grow.

There are days I resent it. Not them—never them—but the fact that my body also asks things I can’t give it. That pain means I move slowly when speed is what the morning requires. That I have to choose between standing long enough to cook or sitting long enough to help with homework, because I can’t do both.

I resent that the world sees my fatigue as moral failure. I resent that there’s no gap between what I can do and what must be done, and when the gap appears anyway, someone suffers for it. That resentment doesn’t last. But it visits. And pretending it doesn’t would be a lie.

There are days when the outside world forces its way in. A doorway that’s almost wide enough but not quite. A staff member who speaks to the wheelchair instead of to the child sitting in it. A room advertised as calm that hums with fluorescent lights. Inclusion printed on a leaflet and undone by a hinge.

People want to know why families stop going to places like these. We don’t stop. We recalculate. We add another line to the list of places that don’t yet know how to have us. And then we try again somewhere else, because the alternative is to shrink until there’s nothing left.

Communication sits at the core. The child who doesn’t speak much isn’t empty.

They’re not a puzzle to be solved by insistence. Their language is pattern and pressure and look and reach. The parent who can’t stand long isn’t withdrawing. They’re choosing where their strength will land so the day doesn’t collapse by afternoon.

Co-existence means learning each other’s grammar without needing to correct it.

It also means admitting the cost. There’s an ache that comes from being misread in public, and another that comes from being misread at home. There’s the guilt of guessing wrong for a child who can’t yet correct you. Also, the thin anger that comes when a form needs you to declare the worst parts of someone you love in order to unlock the smallest help.

These costs don’t cancel. They accumulate. And still, the morning comes, and the house asks the same question it asked yesterday: what would make today possible?

Sometimes the answer is: nothing will. The resources aren’t there. The appointment that would help has a two-year waiting list. The equipment that would make one child’s day bearable costs more than three months’ rent, and the funding application has been refused twice.

You can design all you want. You can read the room, anticipate the pressure points, circulate the roles. But if the system has decided your family doesn’t qualify, or the money isn’t there, or the world outside remains fundamentally unbuilt for you, co-existence becomes damage limitation.

Some days we’re not thriving. We’re just making it to bedtime without anyone getting hurt.

That’s not failure. But it’s also not the version of this life anyone would choose.

People say “coping” as if the goal were to hold still long enough for the hard part to pass.

Co-existence isn’t coping. Coping suggests endurance without change. Co-existence is adaptation without apology.

It refuses the pose of tragedy and the pose of heroism. It’s neither. It’s a practice. A way of standing in the same room with bodies and minds that don’t match and finding a way to stop it imploding.

There are moments of clean joy. A sibling lines up figures on the floor and the brother who rarely notices joins for a count of three. A parent and child sway in a kitchen to a song that’s always the same because the sameness is the point. A joke lands at the exact second a meltdown leans over the edge, and everyone laughs, surprised, because someone they love chose light when gravity pulled dark.

These aren’t consolations. They’re life itself.

To outsiders, a family like mine can look like a lesson in patience. It’s not. It’s a lesson in reading. Read the room for what it asks. Read the person for what they can hold. Read the system for where it’ll fail you and have a plan that doesn’t depend on its promise. We don’t learn these things once. We learn them every week and sometimes every hour.

You can call that relentless. I call it accurate. Because nothing about this is a one-time fix. It can’t be a new timetable. It won’t be a better sticker chart. It’s definitely not a training session delivered on a Tuesday and executed on a Wednesday.

It’s the set of changes that recognise difference as the baseline rather than the exception. It’s the decision to design a day around bodies and minds as they are, not as the form assumes they should be.

People often ask how we do it. The question hides another: why don’t you fall apart? The answer is that we do, and then we don’t. We fall apart and then reassemble. The house is set up to allow both.

We have a corner that’s always quiet because someone will always need quiet. There’s a chair that swivels because turning sometimes makes stillness possible. And of course, a shelf where the same three books live because repetition is comprehension, not delay. None of this is fancy. All of it is intentional.

But there are things we don’t get to do. Spontaneity isn’t available to us the way it is to other families. We can’t decide on a Friday to go somewhere new on Saturday. The risk is too high, the prep too lengthy, the cost of getting it wrong too steep.

We don’t take holidays the way other people do. We don’t go to loud places, or crowded places, or places without a clear exit.

Some of that is choice. Most of it is math. We’ve calculated what each outing costs in energy, in recovery time, in meltdowns we’ll be managing for two days after. Often the equation doesn’t work. Sometimes we stay home. We’re not missing out, exactly. But we are missing.

None of this would be necessary if the world were built differently. If access were assumed, if communication supports were ordinary, if waiting weren’t a weapon. But it’s necessary, so we do it.

Co-existence becomes the method for moving through a world that’s still catching up. It’s how we keep dignity alive in a house where labels multiply, but love isn’t a finite number to be divided.

I return to the word because it deserves to be corrected. Co-existence isn’t neutrality. It’s not two sides eyeing each other across a line. It’s not endurance with gritted teeth. It’s the weave that holds when nothing matches.

The agreement to remain in the same frame even when the picture doesn’t resolve. The practice of designing days that fit the bodies you have, not the bodies a leaflet imagines.

Co-existence is neither a plan nor a theory.

It’s the lived fact that different bodies and different minds share a hallway, a table, a night’s sleep, and don’t need a single person to be the template. It’s not one disabled child inside an otherwise ordinary family. It’s disability braided through every person, in different ways, at different times. Not a problem to manage, but a condition of being together.

That’s what outsiders miss. They think we’re surviving. We’re not. We’re co-existing.

That’s not less than life.

It is life.

That was very well written, thank you for wordings it so well! PROBABLY the best definition of the situation I have ever incounterd. Thank you!